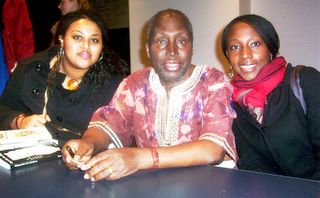

Ngugi wa Thiong'o in Toronto

Ngugi wa Thiong’o:

Kenya’s Literary Giant Talks About His Life as a Writer at University of Toronto

I have been waiting for March 21, 2005 since October 2004 when I first learned that the Department of English at the University of Toronto would be hosting on this day, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Africa’s foremost writer and Kenya’s literary giant, as the last guest speaker in a year-long African writers series.

The wait was well worth it. If you went to high school in Africa you had to read Ngugi wa Thiong’o to pass secondary school. If you read him in Canada he showed you what it means to be an African in the post-colonial era; how being in exile is similar to being in prison. Thiong’o showed the African diaspora and many onlookers the importance of writing, thinking and being political in your own language.

Writing in his native Gikuyu (some translate this Kikuyu), Thiong’o has been one of the foremost theorists in linguistic and cultural resistance to imperialism. He outlined this resistance in the lecture I attended at New College, University of Toronto. This was the awaited lecture. People sat in a jam-packed, technologically deficient lecture hall which would have been called underdeveloped in Africa- but since it was in Canada, it is endearingly considered cozy. Everyone was silent to the point of absurdity; so that we could hang onto Ngugu wa Thiong’o’s every word and movement. This was especially when the masterful playwright performed some of his favourite parts in his many books. Simultaneously, he outlined the path which has shaped his forty-something literary career.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o began writing in the 1960s while still an undergraduate student at Makerere University College. He was a student of English studying, as he put it, "everybody from Shakespeare to T.S. Eliot." At this time, new writers were flourishing in Africa. Thiong’o was inspired by Carribean writers who also helped him understand what had happened and what was continuing to happen during that era of decolonization.

His first novel, The River Between depicts 20th Century Kenya and the first encounter between the British colonizers and the Africans. Thiong’o said the reason why he situated this novel in pre-colonial Kenya was because he saw what the weapon of colonization was. "Colonization..." Thiong’o said authoritatively, "...alienates people from their history. This is the purpose. African writers had to make claim of their history which is why The River Between was set early." Thiong’o wrote his second book Weep Not Child as an undergraduate as well. It was published in 1964 and it was a "collective autobiography"; he was writing about the conditions in Kenya at the time, as well as the 1952 Mau Mau war of independence.

At this point in the lecture, before he went on to describe the publication of his third novel written in Leeds University, UK, A Grain of Wheat, Thiong’o explained the two types of African colonization: a) Protectorate: This was administrative intervention and resource exploitation. i.e. Nigeria, Ghana b) Settler Colonies: Where the colonizers actually settled and made African land their own. i.e. Angola, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Kenya, South Africa, Eritrea, Morocco, Algeria, erc.

In the settler colonies Thiong’o said that the Land question was crucial because it had been taken from Africans. Next was the question of Labour since Africans were then being forced to work and harvest their own land without reaping benefits. Finally, the last important question concerned Language. "Language", said Thiong’o, "was the tool of cultural domination. When you break a language, you break a people." Thiong’o says that his recognition that people were connected through language made him understand the method of colonization: "The colonizers did not take on the language of the colonized on whose land they settled; rather, the colonizers forced the colonized to learn their own language. Kenyans were forced to speak English which kept the ties of colonials to their own homeland in Europe while Africans broke their ties while still living at home."

Fast forward now to 1976. This year something happened which was pivotal to Ngugi’s life and career. He began to work in the community while still a professor at the university. Along with other Kenyan intellectuals, Thiong’o began to work at a Community Cultural Centre. The question that stopped him in his tracks was the beginning of his linguistic and cultural, social and political resistance: what language was to be used in the village communities? The intellectuals could not use English because, as would be expected, none of the villagers spoke it. They had to use Gikuyu, the language of his childhood and the African language of the other villagers. This was a practical question of communication that started out his ideological resistance to writing and publishing in English before his own native language Gikuyu. "How could I tell other authors to write in their language and stay true to their roots if I myself do not do it? I must lead by example," Ngugi said before being honoured with roaring applause.

Writing now foremostly in his native Gikuyu, Thiong’o wrote a play, I’ll Marry When I Want, and it was hugely successful among Kenyans. It challenged traditional conceptions of social life in Africa so it was bound to make the Kenyan establishments nervous. On 16 November 1977 the Kenyan government stopped the play. On 31 December 1977, armed police officers arrested Thiong’o from his home in Gikuyu province and took him to a maximum security prison where he was to spend a year of his life. When Thiong’o recounted this experience he said: " I went from being a professor of literature at the university to a maximum security prison stuck between the condemned and the deranged. Perhaps it was best to be somewhere in between!"

So as part of his resistance, Ngugi wa Thiong’o began to "write in the very language that was the basis of my incarceration." He wanted to distance himself from what had happened to him and from the prison environment; so he wrote. But he was not given paper and pen so what he used was the (very tough and durable!) toilet paper that was handed to prisoners. He wrote his fifth book, Devil on the Cross, while detained without trial. It was published in 1982. This novel is one of the most powerful critiques of modern Kenya ever written.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o gave an inspiring lecture. Often, Thiong’o would be a dramatist, acting out certain scenes from his novels, making the audience laugh excitedly. He answered two questions from the audience, one of which was a heavy question from a bright Zimbabwean girl about his political disposition on the countries that border Kenya; particularly, what did he think about what is happening now in Sudan? His answer was equally heavy. Thiong’o is an Africanist through and through; he noted that suffering is enacted by Africans onto other Africans all the time and that self-victimization needs to stop. He denied the phrases "Maghreb" and "Sub-Saharan Africa" because he says these were designed to separate Africans from themselves, so that we could not recognize each other and our shared histories of success and turmoil. He understands deeply the horror and political instability due to ethnic conflict (more appropriately, genocide) and he said it is the writer’s job to be the creative force in society. I will leave you now with his words which I scribbled down frantically :

I have been waiting for March 21, 2005 since October 2004 when I first learned that the Department of English at the University of Toronto would be hosting on this day, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Africa’s foremost writer and Kenya’s literary giant, as the last guest speaker in a year-long African writers series.

The wait was well worth it. If you went to high school in Africa you had to read Ngugi wa Thiong’o to pass secondary school. If you read him in Canada he showed you what it means to be an African in the post-colonial era; how being in exile is similar to being in prison. Thiong’o showed the African diaspora and many onlookers the importance of writing, thinking and being political in your own language.

Writing in his native Gikuyu (some translate this Kikuyu), Thiong’o has been one of the foremost theorists in linguistic and cultural resistance to imperialism. He outlined this resistance in the lecture I attended at New College, University of Toronto. This was the awaited lecture. People sat in a jam-packed, technologically deficient lecture hall which would have been called underdeveloped in Africa- but since it was in Canada, it is endearingly considered cozy. Everyone was silent to the point of absurdity; so that we could hang onto Ngugu wa Thiong’o’s every word and movement. This was especially when the masterful playwright performed some of his favourite parts in his many books. Simultaneously, he outlined the path which has shaped his forty-something literary career.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o began writing in the 1960s while still an undergraduate student at Makerere University College. He was a student of English studying, as he put it, "everybody from Shakespeare to T.S. Eliot." At this time, new writers were flourishing in Africa. Thiong’o was inspired by Carribean writers who also helped him understand what had happened and what was continuing to happen during that era of decolonization.

His first novel, The River Between depicts 20th Century Kenya and the first encounter between the British colonizers and the Africans. Thiong’o said the reason why he situated this novel in pre-colonial Kenya was because he saw what the weapon of colonization was. "Colonization..." Thiong’o said authoritatively, "...alienates people from their history. This is the purpose. African writers had to make claim of their history which is why The River Between was set early." Thiong’o wrote his second book Weep Not Child as an undergraduate as well. It was published in 1964 and it was a "collective autobiography"; he was writing about the conditions in Kenya at the time, as well as the 1952 Mau Mau war of independence.

At this point in the lecture, before he went on to describe the publication of his third novel written in Leeds University, UK, A Grain of Wheat, Thiong’o explained the two types of African colonization: a) Protectorate: This was administrative intervention and resource exploitation. i.e. Nigeria, Ghana b) Settler Colonies: Where the colonizers actually settled and made African land their own. i.e. Angola, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Kenya, South Africa, Eritrea, Morocco, Algeria, erc.

In the settler colonies Thiong’o said that the Land question was crucial because it had been taken from Africans. Next was the question of Labour since Africans were then being forced to work and harvest their own land without reaping benefits. Finally, the last important question concerned Language. "Language", said Thiong’o, "was the tool of cultural domination. When you break a language, you break a people." Thiong’o says that his recognition that people were connected through language made him understand the method of colonization: "The colonizers did not take on the language of the colonized on whose land they settled; rather, the colonizers forced the colonized to learn their own language. Kenyans were forced to speak English which kept the ties of colonials to their own homeland in Europe while Africans broke their ties while still living at home."

Fast forward now to 1976. This year something happened which was pivotal to Ngugi’s life and career. He began to work in the community while still a professor at the university. Along with other Kenyan intellectuals, Thiong’o began to work at a Community Cultural Centre. The question that stopped him in his tracks was the beginning of his linguistic and cultural, social and political resistance: what language was to be used in the village communities? The intellectuals could not use English because, as would be expected, none of the villagers spoke it. They had to use Gikuyu, the language of his childhood and the African language of the other villagers. This was a practical question of communication that started out his ideological resistance to writing and publishing in English before his own native language Gikuyu. "How could I tell other authors to write in their language and stay true to their roots if I myself do not do it? I must lead by example," Ngugi said before being honoured with roaring applause.

Writing now foremostly in his native Gikuyu, Thiong’o wrote a play, I’ll Marry When I Want, and it was hugely successful among Kenyans. It challenged traditional conceptions of social life in Africa so it was bound to make the Kenyan establishments nervous. On 16 November 1977 the Kenyan government stopped the play. On 31 December 1977, armed police officers arrested Thiong’o from his home in Gikuyu province and took him to a maximum security prison where he was to spend a year of his life. When Thiong’o recounted this experience he said: " I went from being a professor of literature at the university to a maximum security prison stuck between the condemned and the deranged. Perhaps it was best to be somewhere in between!"

So as part of his resistance, Ngugi wa Thiong’o began to "write in the very language that was the basis of my incarceration." He wanted to distance himself from what had happened to him and from the prison environment; so he wrote. But he was not given paper and pen so what he used was the (very tough and durable!) toilet paper that was handed to prisoners. He wrote his fifth book, Devil on the Cross, while detained without trial. It was published in 1982. This novel is one of the most powerful critiques of modern Kenya ever written.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o gave an inspiring lecture. Often, Thiong’o would be a dramatist, acting out certain scenes from his novels, making the audience laugh excitedly. He answered two questions from the audience, one of which was a heavy question from a bright Zimbabwean girl about his political disposition on the countries that border Kenya; particularly, what did he think about what is happening now in Sudan? His answer was equally heavy. Thiong’o is an Africanist through and through; he noted that suffering is enacted by Africans onto other Africans all the time and that self-victimization needs to stop. He denied the phrases "Maghreb" and "Sub-Saharan Africa" because he says these were designed to separate Africans from themselves, so that we could not recognize each other and our shared histories of success and turmoil. He understands deeply the horror and political instability due to ethnic conflict (more appropriately, genocide) and he said it is the writer’s job to be the creative force in society. I will leave you now with his words which I scribbled down frantically :

"The word becomes a threat when it becomes flesh. When the word is disembodied it is not a threat. Embodied words are a creative force in society. Writers must make words a creative force in all societies. To do anything else would mean that we have ceased to be writers. Intellectuals have always been imprisoned for their words. Think back to the Ancient Greek times and the trial of Socrates. South African writers and Eastern European writers have also been targeted. This is a trend revealing that the word is a creative force and that society views this force as a threat. We should continue to write even when the consequences may be prison, exile or even death."

3 Comments:

Salaams/Peace

A review of 'Britain's Gulag: the brutal end of empire in Kenya' by Caroline Elkins:

http://enjoyment.independent.co.uk/books/reviews/story.jsp?story=602876

Wasalaam

Yakoub

great stuff kiddo!! I read "weep not child" in secondary school. make a huge impact on me. long live the legend

Ngugi shows how to tackle a big problem facing the african race .

How to convey intellect in our languages . This will allow us to resist cultural domination and all the baggage that brings. WELL DONE!

Post a Comment

<< Home